What Does The British Queen Have To Do With Chemistry?

A week ago, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II celebrated 63 years of reigning on the British throne. Do you know what this event has to do with chemistry? I’ll give you a hint: the Robe of Purple Velvet, a traditional coronation dress of the British Monarchs

##The Story Of One Scientific Mishap

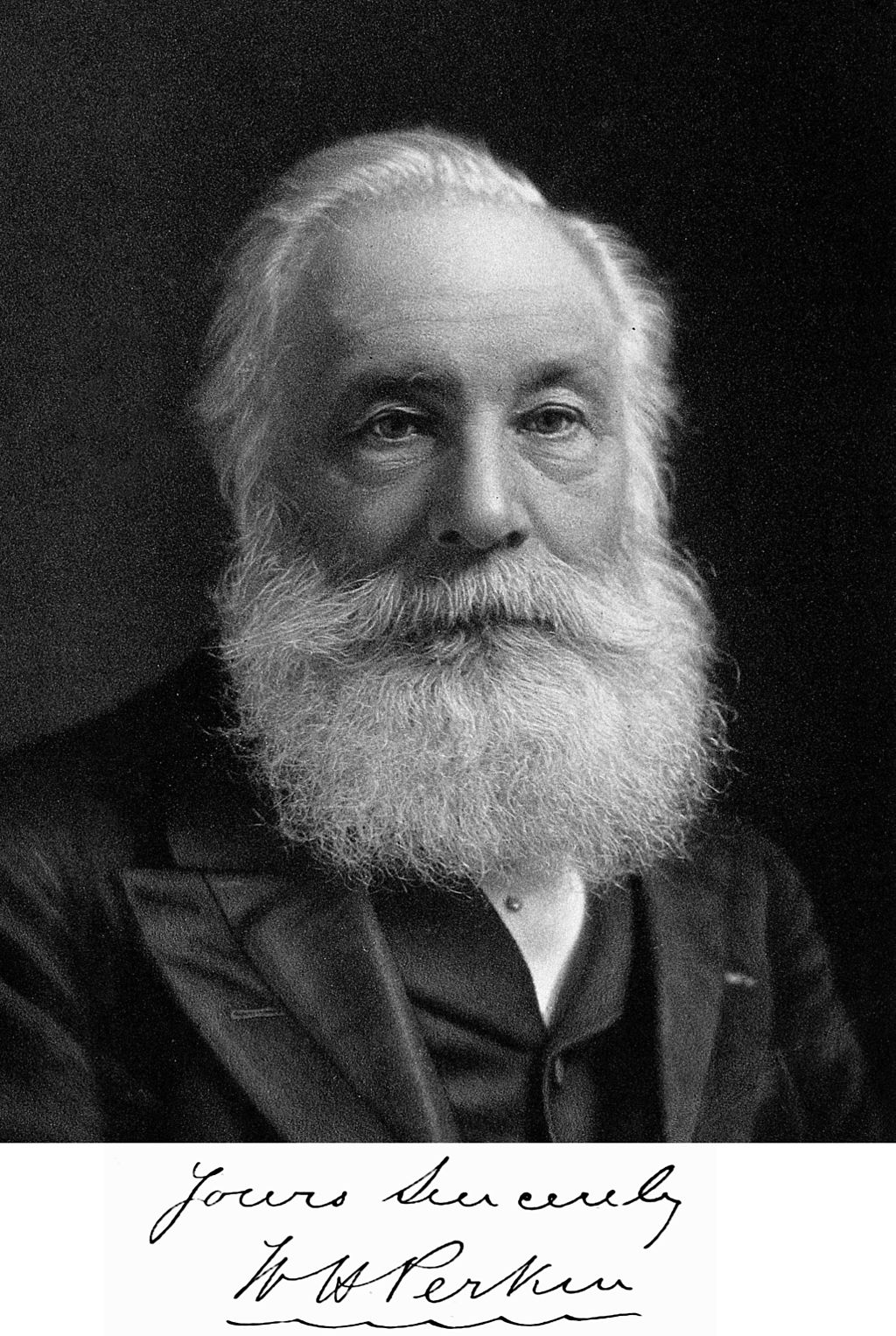

This is a story of the color purple, which for centuries has been associated with power, wealth and royalty. A story about a man who made a fortune out of a scientific mishap. The man’s name is Sir William Henry Perkin. The mishap, which gave birth to the synthetic dye industry and made Perkin famous, is mauveine — a purple aniline dye. Judging by the history of scientific discoveries, I am convinced: you have to try hard to make one. This often equates to a life-long adventure of painstakingly daunting work, sleepless nights, and excruciating headaches you get from banging your head against the wall every time things do not work. On occasion, however, when all hell breaks loose, you get lucky and — voilà — get famous overnight! The world has certainly seen quite a few of such cases: from the discovery of penicillin in a dirty petri dish to the tiny “smart” sensors in the shattered silicon chip. It happened to a man named William Henry Perkin too. Back in 1856 when he just turned 18.

What Is The Story? What Did Perkin Discover?

A young protégé of August von Hofmann, a famous German chemist of that era, Perkin was trying to synthesize an antimalarial compound using aniline — a substance derived from coal tar. One day, he accidentally discovered a dark sludge at the bottom of the flask. While he knew it wasn’t what he was aiming for, he did not throw it away. Instead, he wisely mixed it with alcohol. The resultant solution dyed a piece of silk bright and fade-resistant purple

Image by Drdoht.

The moment he saw it, he knew it was a revolution or a profitable business at the very least. Ever since the first Romans, the world’s rich and privileged have been obsessed with purple color, but extracting it from natural sources was a pain in the neck. Imagine boiling 20,000 snails for many days to prepare enough dye to color one royal toga! Not that the rich and privileged cared, but Perkin certainly did.

After learning about the discovery, however, Hofmann famously shrugged his disapproving “Purple sludge!” and turned away. That did not stop stubborn Perkin from moving forward and building a successful enterprise that brought him fame and lots of money, and the world — fashionable and affordable purple fabrics. He called the dye aniline purple, or mauveine

Image by Boonekamp.

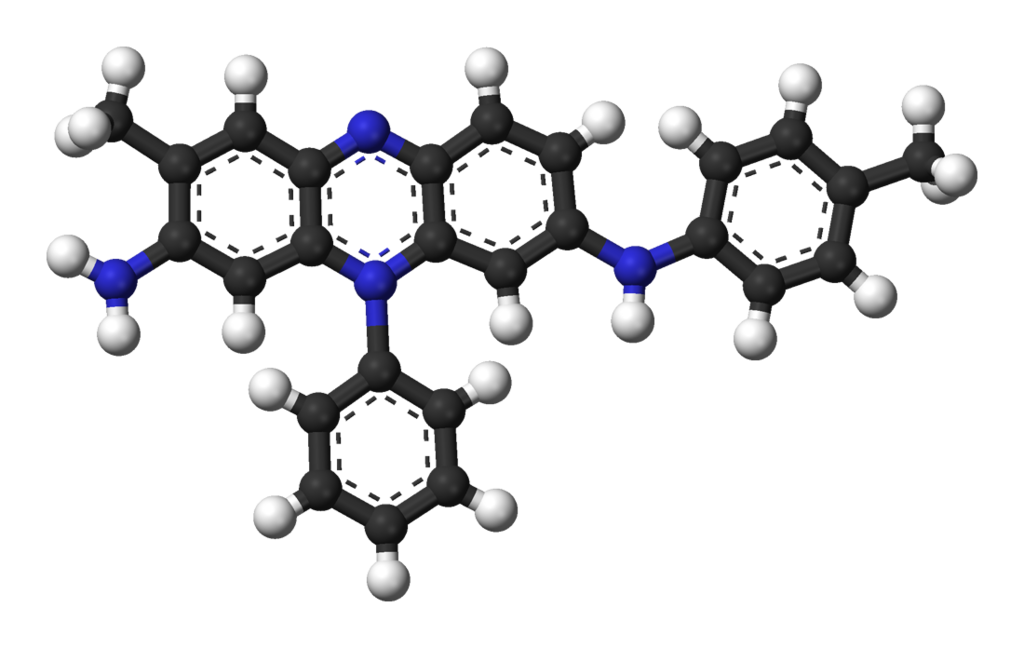

And why exactly is mauveine purple?

Same reason why carrots are orange and tomatoes are red. The origin of the color is in the structure — or in the bonds and electrons, to be precise.

Image by Benjah-bmm27.

See the dash lines in the molecule of mauveine? This is what chemists use to indicate the promiscuous electrons that spread over a number of adjacent atoms. The bonds, over which the electrons are spread, are called conjugated. And the more there are, the more freely the electrons can move. As a result, it takes less effort to excite them and they can absorb low-energy light. Mauveine looks purple because his promiscuous electrons absorb the yellow-green portion of the visible light. The reflected red and blue, when processed by our eyes and brain, become color-coded as purple. You can learn more about light and color in this video:

What about the broader impact of the discovery? Was it huge?

It certainly was, considering how quickly it galvanized the production of new dyes, cosmetics, perfume, fertilizers, and pesticides. It practically laid the foundation of the chemical industry and such giants as BASF, AGFA, and Bayer. It inspired scientists like Paul Enhrlich to perform research on staining animal tissues and microorganisms, which later fueled chemotherapy. It was huge, indeed. And Perkin knew it would be. He knew it when, in less than a year, mauveine became a buzzword in the fashion industry. He knew it when his skeptical former advisor got interested in the aniline dyes. And he knew it when he got invited to give a talk at the Royal Academy of Sciences. Michael Faraday, the father of electricity, was among the people in the audience. Perkin was 23 when he gave that talk. Five years earlier, he was just an unknown student experimenting with aniline in his home lab. At that time, he was the one to attend Faraday’s talks.

So next time you see a purple fabric – remember the story. Chemistry is full of such twists, and, after all, is profoundly beautiful. Very often it is also brightly colored Here is a bonus video for you to enjoy:

See also

CASE STUDY - 8th Grade students at St Timothy's Catholic School use MEL Chemistry to enhance their science lessons

Saint Timothy Catholic School in Mesa is committed to promoting academic excellence in each child it looks after. They encourage self-discipline, self-respect, and respect for others. They understand the importance of engaging students in a comprehensive and relevant curriculum. As a result, the middle school science teacher from St. Timothy Catholic School is using MEL Chemistry subscriptions to enhance and expand their range of learning activities.

CASE STUDY - MEL Chemistry allowing pupils to reach their full potential

The Empower Learning Center is the Alternative Learning Program (ALP) within the Hinckley-Finlayson School District. They offer non-traditional education options for students ages 16-21 in their daytime program, night school for traditional high school students who need to make up credits, and night school for adults 18 and older who would like to complete their diploma or equivalency.

The school was seeking engaging, hands-on chemistry kits to make their science classes more interactive, and to help their students understand key science concepts and achieve their full potential in chemistry.

CASE STUDY - MEL Chemistry at Lund International School, Sweden

Emma Taylor, a science teacher at Lund International School (Sweden), has chosen MEL Chemistry sets as the best option for her students’ science classes. In Lund International School, all programmes are taught in English, and having chemistry sets in English are a great asset to accompany science classes.

Here, Emma shares her experience of how MEL Chemistry sets improved her students’ comprehension and understanding of science concepts.