A hope to fight antibiotic-resistant infections

A new study published in Nature this week describes a new class of antibiotics that bacteria are not yet resistant to. This is an important break-through because the last class of antibiotics was found nearly 30 years ago. How do antibiotics work? How do bacteria acquire resistance to antibiotics?

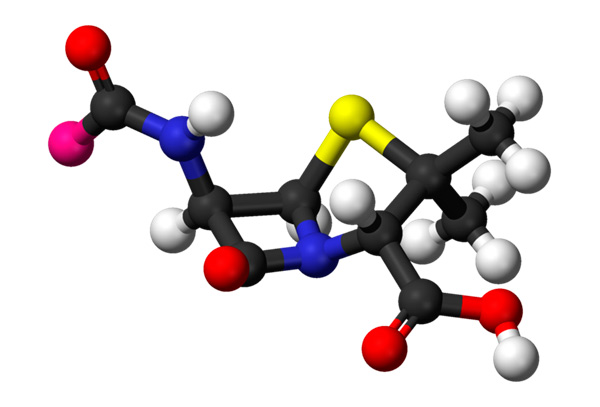

Antibiotics are chemical compounds killing or slowing down the growth of bacterial cells. The first antibiotic, ampicillin, was discovered by Alexander Fleming and purified for medical purposes by Howard Florey’s team in 1940s:

Since then, many lethal infections, such as pneumonia, cholera, tuberculosis and meningitis could be cured. However, the bacterial empire strikes back and many microorganisms are now developing resistance to common antibiotics used in in clinical practice. This is one of the biggest medical problems: in USA alone, more than 20 000 people die from infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria each year. How do antibiotics work and what makes bacteria resistant?

Modes of antibiotic action

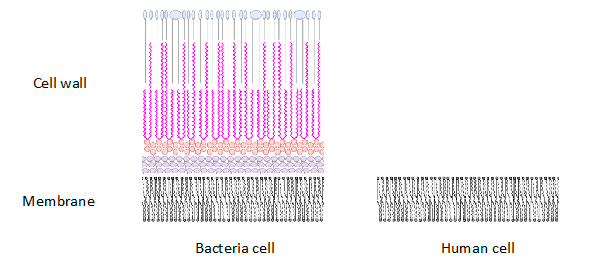

Antibiotics attack structures or molecules that are different in humans and microorganisms. Most common target of antibiotics is cell wall. In addition to cell membrane, bacteria have a stiff wall serving to protect them from destruction caused by internal pressure. It is made of chains of carbohydrates linked together by short peptides.

Many antibiotics, such as ampicillin, block the activity of enzymes needed for cell wall formation. Because human cells do not have cell walls, the antibiotics do not affect them.

Mechanisms of anibiotic resistance

Living organisms adapt to the environment and it is no surprise that bacteria started to develop resistance to antibiotics. To understand the mechanisms of antibiotic resistance, let us go back to ampicillin. As we described above, it prevents the formation of the cell wall. This usually kills bacteria but some species have a protein that breaks down ampicillin and other antibiotics having similar chemical structure. This protein, called beta-lactamase, is what makes bacteria resistant. It turned out that bacteria could transfer beta-lactamase gene to another bacteria. How does this happen?

In addition to chromosomal DNA, bacteria can possess small circular DNA molecules carrying several genes and sequences allowing them to be transferred from one cell to another. This transfer happens when two different cells, not necessarily belonging to the same species, come close to each other and form a bridge through which these circular DNAs diffuse to another cell. This mechanism, along with others, allows bacteria to acquire resistance to antibiotics.

Find out more about other mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in this movie:

What did the new study do to deal with antibiotic resistance?

The scientists discovered a new type of antibiotic that bacteria are not yet resistant to. This is an important break-through because the last class of antibiotics was found nearly 30 years ago. The difficulty to discover new classes comes from the fact that most of the antibiotics were extracted from microorganisms living in soil. However, only a small fraction (around 1%) of soil microorganisms could have been cultured in laboratory conditions. To overcome this problem, Losee Ling and colleagues applied technology, allowing cultivating many more types of soil bacteria directly in their natural environment. Using this technology they extracted new potential antibiotic, which they termed teixobactin. It was tested on mice and turned out to be non-harmful to mammalian cells. Teixobactin acts by inhibiting cell wall synthesis.

What’s next?

Teixobactin was so far tested on rodents. Next steps are:

- To start medical trials and test whether it is effective in humans

- To rule out any potential harm it can cause

If everything goes well, we can expect that a new class of antibiotic will be available in the next 5 years.

Read more about teixobactin in this BBC article.

See also

CASE STUDY - 8th Grade students at St Timothy's Catholic School use MEL Chemistry to enhance their science lessons

Saint Timothy Catholic School in Mesa is committed to promoting academic excellence in each child it looks after. They encourage self-discipline, self-respect, and respect for others. They understand the importance of engaging students in a comprehensive and relevant curriculum. As a result, the middle school science teacher from St. Timothy Catholic School is using MEL Chemistry subscriptions to enhance and expand their range of learning activities.

CASE STUDY - MEL Chemistry allowing pupils to reach their full potential

The Empower Learning Center is the Alternative Learning Program (ALP) within the Hinckley-Finlayson School District. They offer non-traditional education options for students ages 16-21 in their daytime program, night school for traditional high school students who need to make up credits, and night school for adults 18 and older who would like to complete their diploma or equivalency.

The school was seeking engaging, hands-on chemistry kits to make their science classes more interactive, and to help their students understand key science concepts and achieve their full potential in chemistry.

CASE STUDY - MEL Chemistry at Lund International School, Sweden

Emma Taylor, a science teacher at Lund International School (Sweden), has chosen MEL Chemistry sets as the best option for her students’ science classes. In Lund International School, all programmes are taught in English, and having chemistry sets in English are a great asset to accompany science classes.

Here, Emma shares her experience of how MEL Chemistry sets improved her students’ comprehension and understanding of science concepts.